art as research

As an artist and researcher, my project explores how contemporary art can give us insight into the lived-in experience of artists with Eating Disorders. ‘The Starving Artist’ takes on an autoethnographic approach in specifically addressing my own experience as well as understanding how other contemporary artists with Eating Disorder experience; and examine the complexity and depth of living with this mental illness.

My doctorate study seeks to addrees the central research question:

To what extent can contemporary art concerning eating disorders and distorted body image enlighten us about perceptions of self-identity within a broader context of mental health and well-being?

My doctorate study seeks to addrees the central research question:

To what extent can contemporary art concerning eating disorders and distorted body image enlighten us about perceptions of self-identity within a broader context of mental health and well-being?

Image Still ArtHouse Jersey

Introduction

It has become apparent, that Eating Disorders are not well understood and are often misrepresented within contemporary society and mainstream media (Betterton, 1996; Mental Health Foundation, 2019). The misunderstanding of Eating Disorders lies in the perception that the Disorder involves a predominant focus on dissatisfaction with the individual’s physique, which in turn, leads to negative perceptions of their overall self-image (Anitha, 2019). While these physical manifestations attributed to the countless individuals experiencing Eating Disorders are important. According to Ricardo Dalle-Grave (2011), these physical manifestations are the symptoms and not the causes of the Eating Disorders. This study, therefore, engages in the fields of visual art and health to foreground the direct associations between eating disorders and mental health, which is often omitted, misrepresented, or not widely portrayed (Brian,2006)

My project intentionally draws on the art field to bridge a ‘gap’ in the issue of addressing Eating Disorders. That is, while the medical field provides a lot of insight into the critical diagnosis of Eating Disorders, it can neglect the human experience such as the ‘feeling of being Anorexic’ (Blackburn et al., 2012). These felt experiences vary and can impact the recovery process (Blackburn et al., 2012). Some examples of these experiential facets may include being ‘othered’ through social isolation; an emotional detachment from loved ones and personal interests as well as their subjective sense of being ‘confined’ in a predetermined body shape and gender (Brian, 2006). Contemporary art can therefore play a significant role in representing the experiential and emotionally charged facets of artists living with an eating disorder within this work. This will be achieved through first-hand artistic representations providing insights into the subjective emotive and thinking processes that lie beneath the experience of the illness and humanising mental health illness.

Luisa Callegari Untitled Photography, 2016

Research Areas

My study includes three key research areas:the sexualised body, the abject body, and the embodied/amalgamated body. These three areas were specifically chosen due to their lack of current discourse concerning eating disorders, and the wide scale applicability of their ‘lived-in experience’ of Eating Disorders. Furthermore, these research areas are deeply connected to the central premise of the study and provide insights into the diversity of understanding of this disease.

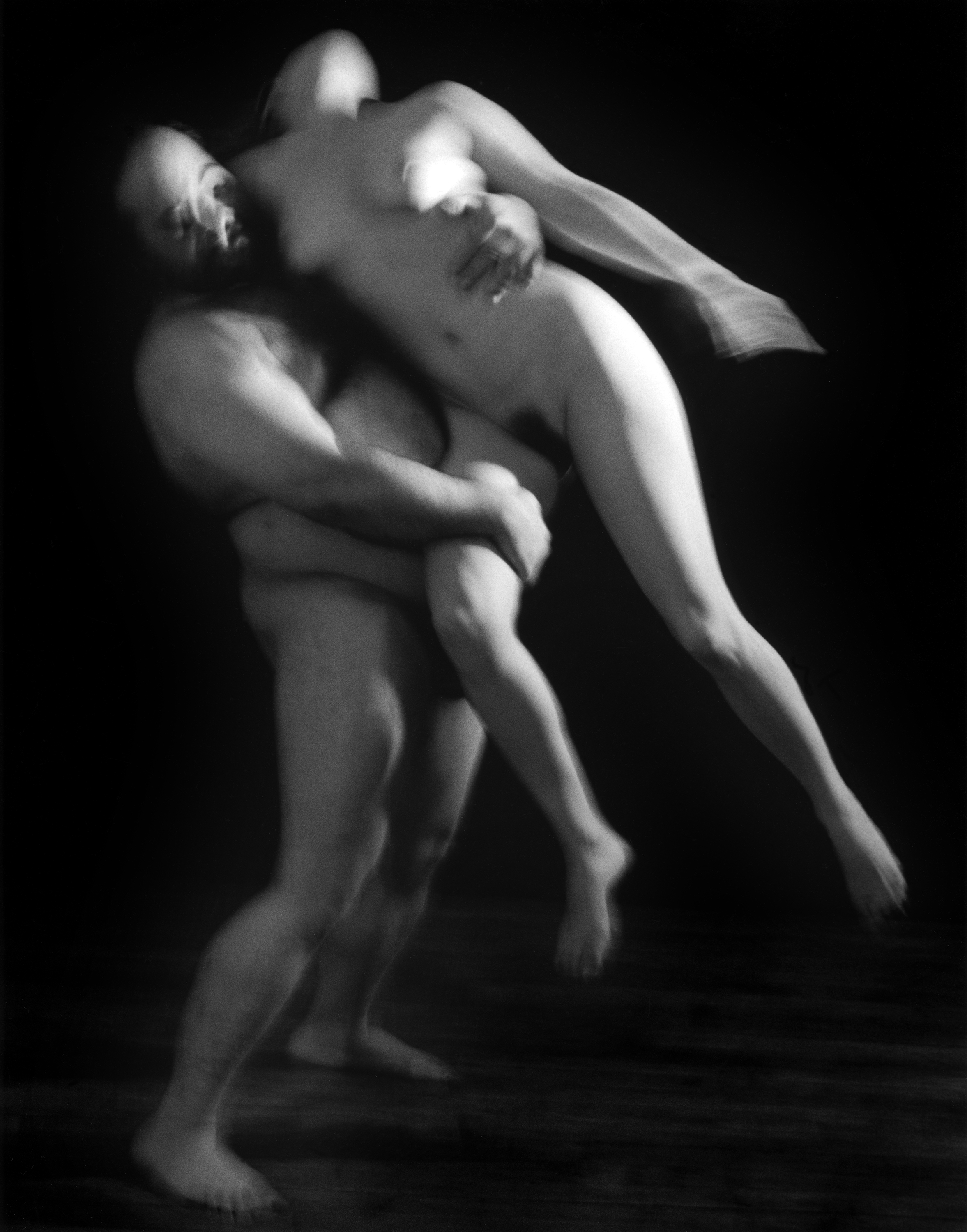

Sexualized Body

Within visual culture, the female body has been explored as well as exploited and objectified for centuries (Brian, 2006; Hoaxx, 1999). Female bodies have served as allegorical figures such as the maternal goddess that has been overtly sexualised and objectified (Hoaxx, 1999). These female figures depict concepts of beauty idea as one that reinforce a societal striving for idealistic perfection of the female body (Brian, 2006). As John Berger (1972) iterates:

“To be naked is to be oneself. To be nude is to be seen naked by others

and yet not recognized for oneself. A naked body has to be seen as an object to become a

nude” (p. 54).

In this context, nudity is sexualised, whereby women are conditioned to satisfy men’s desire to see themselves as desirable(Berger, 1972). Berger’s seminal text operates with a binary gendered discourse. He outlines the gendered power dynamic in the act of looking like the masculine (sexualised) gaze. He explains the power dynamic of the gaze when women are being watched by men. These men are spectators of a woman’s body, which objectifies women (Berger, 1972).

Ariane Lopez-Huici, Holly & Valeria, 1998

Abject Body

Kiki Smith, Tale, 1992

The idea of the abject is key to thinking beyond the dominant media fascination with the Anorexic body as an object of disgust (Ferreday, 2012). Kristeva's theory of Abjection iterates the notion of Abjection as subjective horror. This abjection is the feeling when an individual experiences or is confronted by "corporeal reality" (Kristeva, 1982). Abjection can help reposition people from looking in which healthiness is constituted through a reaction of disgust to the thin body, my point of divergence is to exemplify disgust experienced by Anorexics themselves and is constitutive of Anorexic subjectivity (Ferreday, 2012).

Embodied and Amalgamated Body

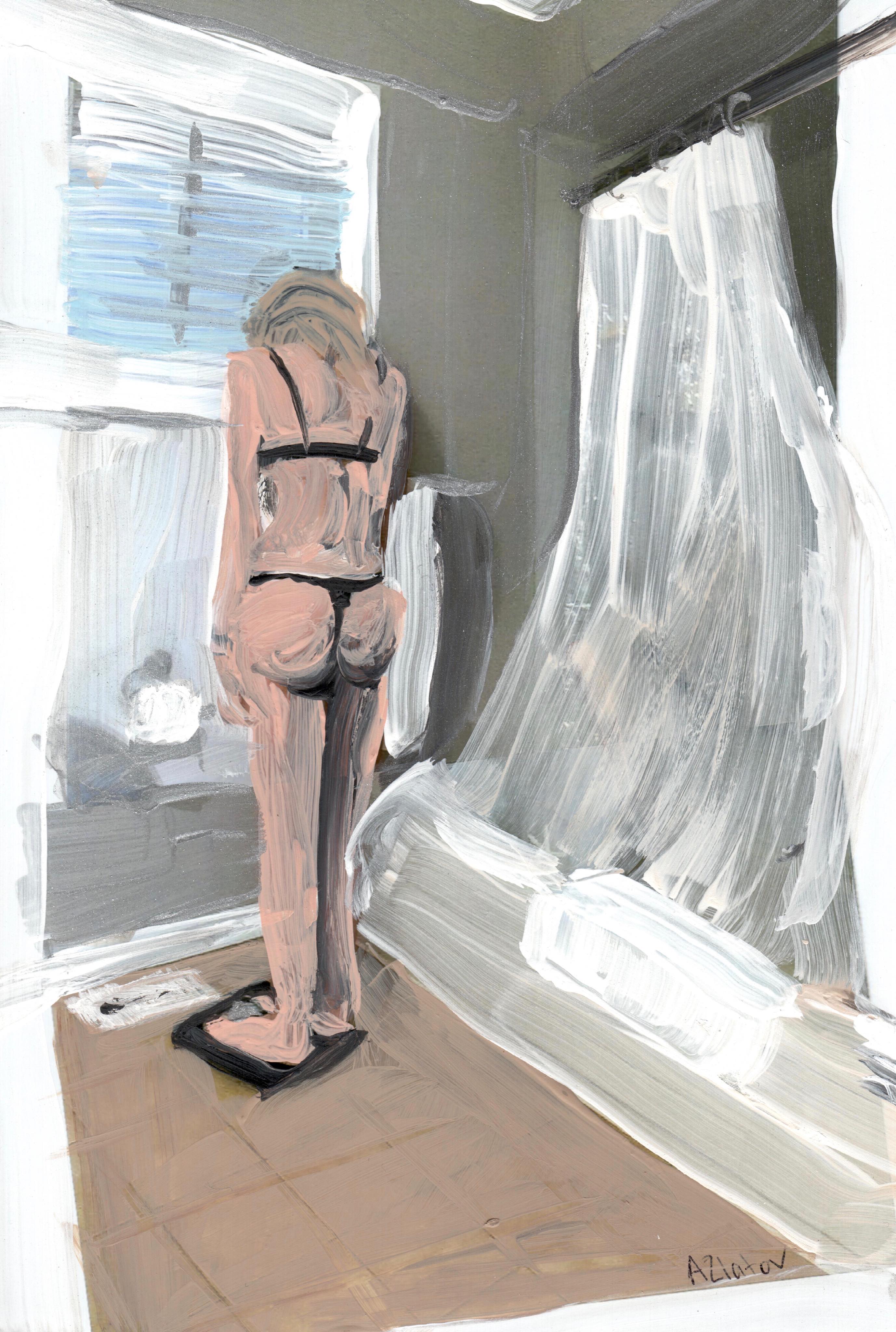

Ally Zlatar, Live and Die By The Scale, Acrylic , 6x4” 2022

One might claim that embodiment is what makes cognition possible by having both the mind and body components interacting dualistically, (Descartes , 1641; Marchant, 2016). However, embodiment, in Csordas’ view, is beyond or additive to the physical body and is a conception focused on how people ‘inhabit’ their bodies. He argues ‘existential ground of culture’ is the body. Thus, embodiment is not simply the mind living in the body, but the social and intersubjective being experienced.

Embodiment contains social, cultural, and perceptual dimensions leading toward Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenological account and of experiential existence being one that is obfuscating mind-body dualism because it is the person/entity versus the social world (Moya, 2014). This is the case because there is no demarcated and bounded individual in this interpretation. Feminist philosopher Elizabeth Grosz articulates the value of embodied subjectivity as:

Embodiment contains social, cultural, and perceptual dimensions leading toward Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenological account and of experiential existence being one that is obfuscating mind-body dualism because it is the person/entity versus the social world (Moya, 2014). This is the case because there is no demarcated and bounded individual in this interpretation. Feminist philosopher Elizabeth Grosz articulates the value of embodied subjectivity as:

“not as the combination of psychical depth and a corporeal superficiality but as a surface whose inscriptions and rotations in three-dimensional space produce all the effects of depth […] understood as fully material and for materiality to be extended and to include and explain the operations of language, desire, and significance” (Grosz, 1994, p.46).

Perhaps it could view this in terms of amalgamation which allows two or more bodies to cooperate and continue as one entity. It is this depth and complex view of how we may be embodied that creates a new form of experiential existence that shapes how the whole person’s being-body in the world can add a new depth to understanding when applied to ‘mental’ wellbeing (Grosz, 1994).

Methodology

The practice-led research originates from my struggles with Anorexia Nervosa. For such a long time, I was trapped in my body and my illness. I could not walk up a flight of stairs because my body was so frail. I had severe osteoporosis and each step caused my back and knees tremendous pain by the 10th step, I would almost faint. Physically I was exhausted, but mentally I was telling myself I was not thin enough – I was not sick enough. I thought there was no escape, or that I would never be content with my physical appearance. I thought it was better to die trying to be thin than to live fat. I wanted to employ a research methodology that would go beyond the trivial scope of external perception of the illness but utilize a methodology that would capture the depths of the struggle.

This practical-led study incorporatesthe importance of autoethnography and the role of myself an insider-researcher. This methodology involves the researcher-practitioner intentionally immersing themselves in theory and practice as a way of gaining insight (McIlveen, 2008). Rather than being an autobiographical account, as McIlveen points out, autoetnography is about being ‘fully immersed’ in the visual and sensory experience of where the knowledge is uncovered (p. 6). This research strategy strives to reassess aspects of human experience best represented by images and writing, and a related analysis of the relationship between the visual and other experiences (McIlveen, 2008).

Image From ArtHouse Holland

Autoethnography

In turn, Autoethnography aids in questioning the impact of someone's illness based on socialised experiences and how a label of being ill can relate to intrinsic self-worth (Mertens, 2010). By being embodied by an illness, one can examine how we were before and after the diagnosis, or how a label can affect our identity and perception of ourselves. For my self-investigation, I chose to use an Autoethnographic inquiry as a specific lens because the methodology was an ideal avenue for me to take as I shared memories and illuminates the critical issues of understanding and portraying eating disorders through an insider perspective.

I discovered subtle ways in which Eating Disorder messages were woven throughout all my life experiences, and the Autoethnographic inquiry not only served to explore the content of their stories, but it also made it possible to examine how myself both as a person and as an artist understands, experiences, constructs, and narrates my experiences.

Insider Researcher

My creative research takes on a unique exploration of my position as an artist and curator experiencing a series of lifelong Eating Disorders. The personal artist’s works not only document ideas that were developed through reflexive practice from my engagement with academic texts, literature, artists’ interviews, and other experiences but will also integrate with my autoethnographic data in this research. It is the foundation of the output. As Graeme Sullivan states, reflexive practice is a research activity that helps create transformative research through seeing the subject in new ways (Sullivan, 2005).

From my research, Eating Disorders in art is limited and has been from an outsider perspective rather than from individual experiencing Eating Disorders directly (Rodgers, 2016). The outsider researcher approach is problematic, not only due to the researcher being removed from the contextual understanding of what it feels to live with an eating disorder but also because it can exclude those who have the Disorder by perceiving these individuals as ill and therefore unfit to contribute to the conversation of Eating Disorders (Dywer, 2009; Sassenrath, 2017).

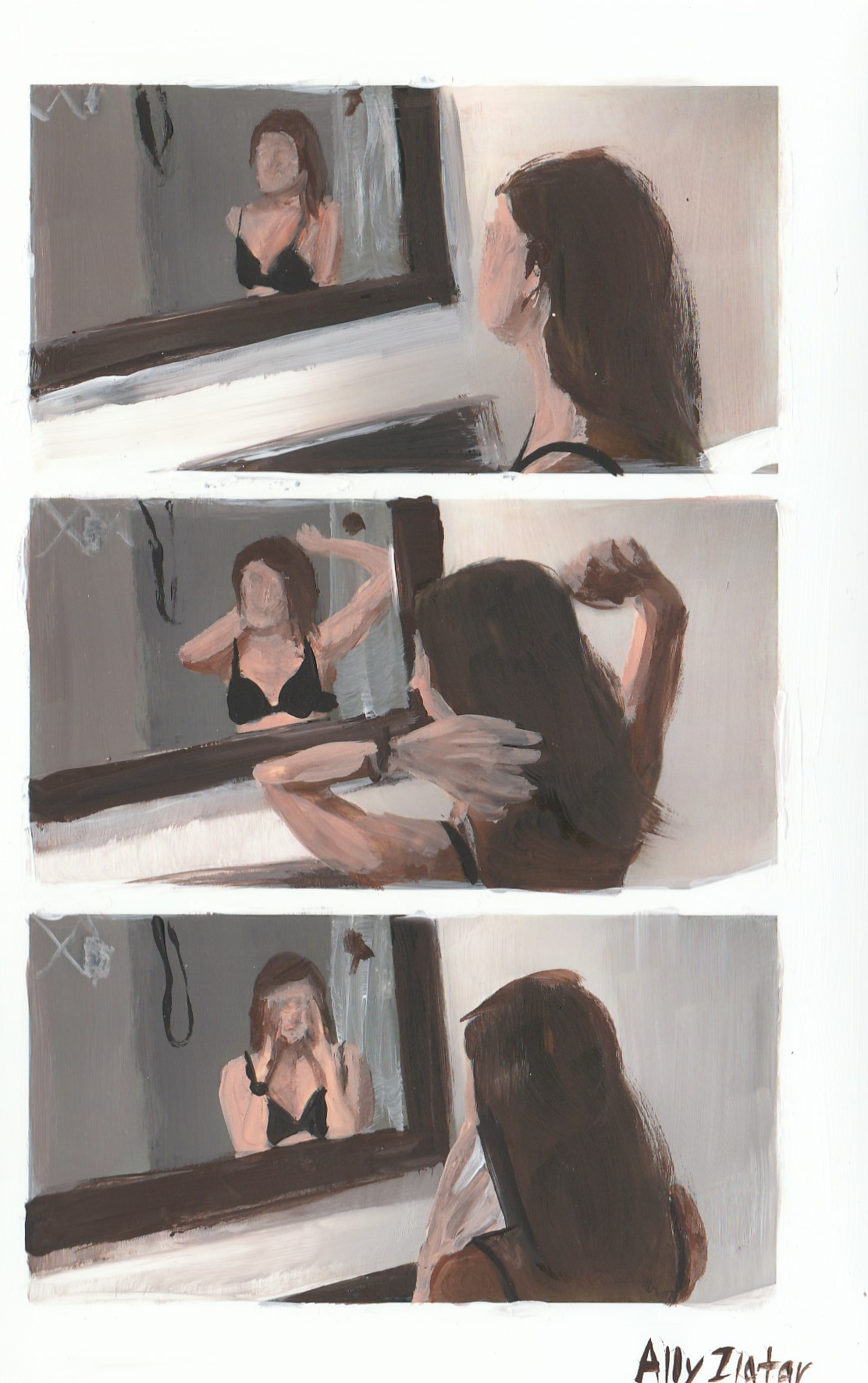

Ally Zlatar, I can’t make me love myself, Acrylic, 2022

Methods & Data Collection

Reflective and Reflexive Journaling

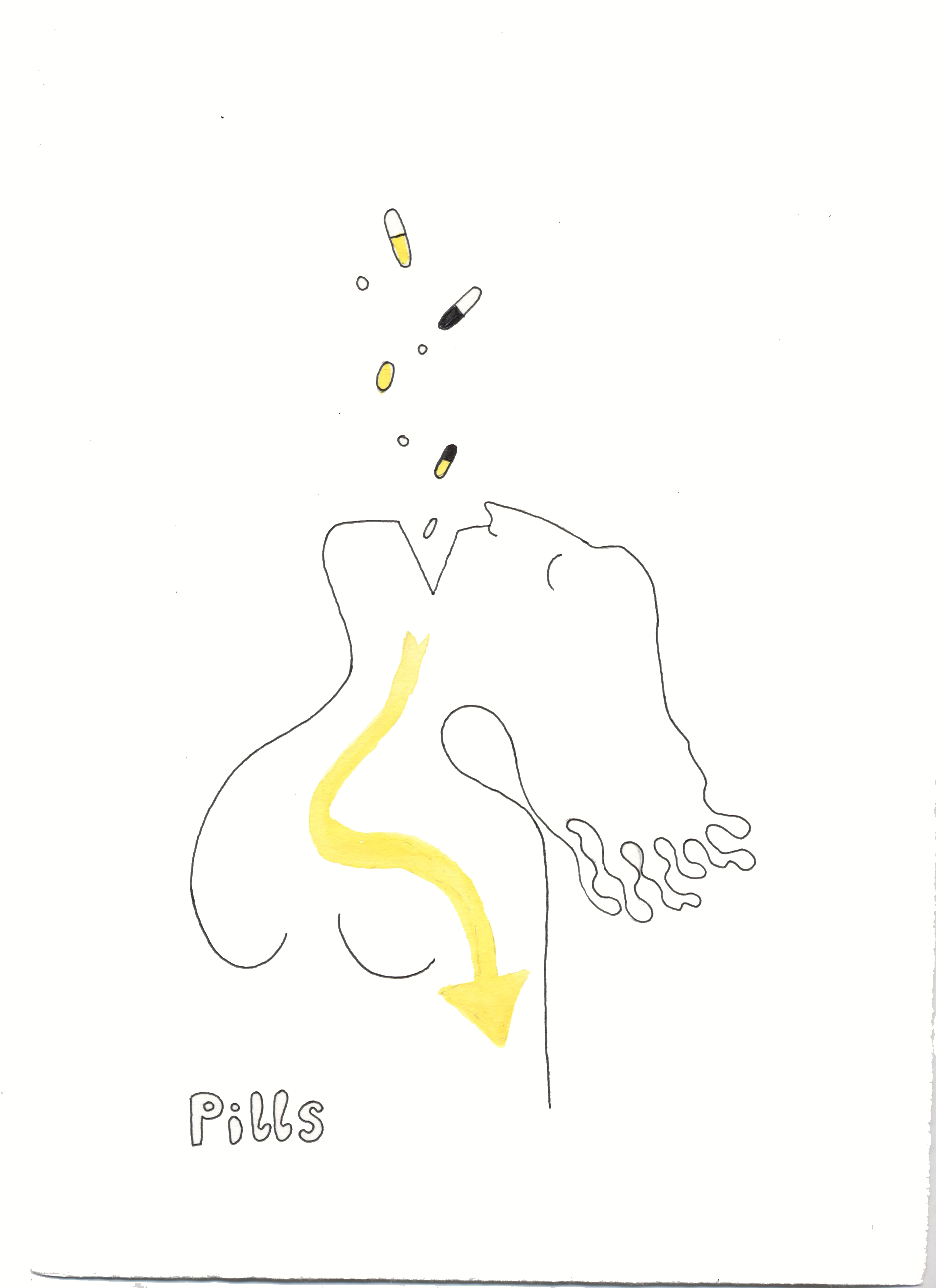

Derived from my autoethnographic artist experience living with Eating Disorders. The personal artist journal will document my ideas as they progress from my engagement with artists with Eating Disorders, medical experts, and literature about Eating Disorders. Additionally, an art journal will enable me to cross-examine academic benchmarks with art production (Bacon, 2014). My works will focus on creating art that will address the themes and gaps concerning the complexity and depth behind the mind of someone who suffers from an Eating Disorder that I think needs closer examination.

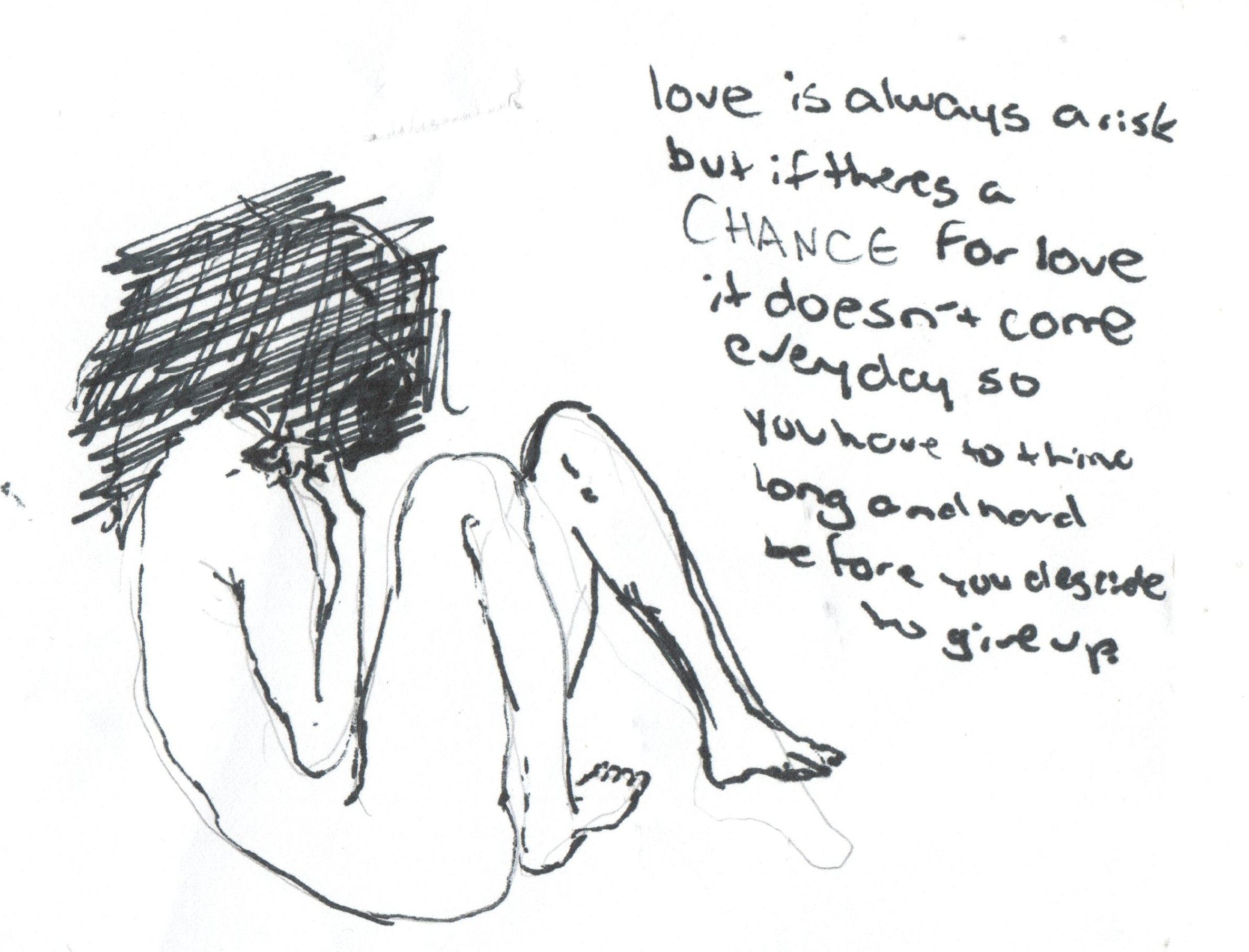

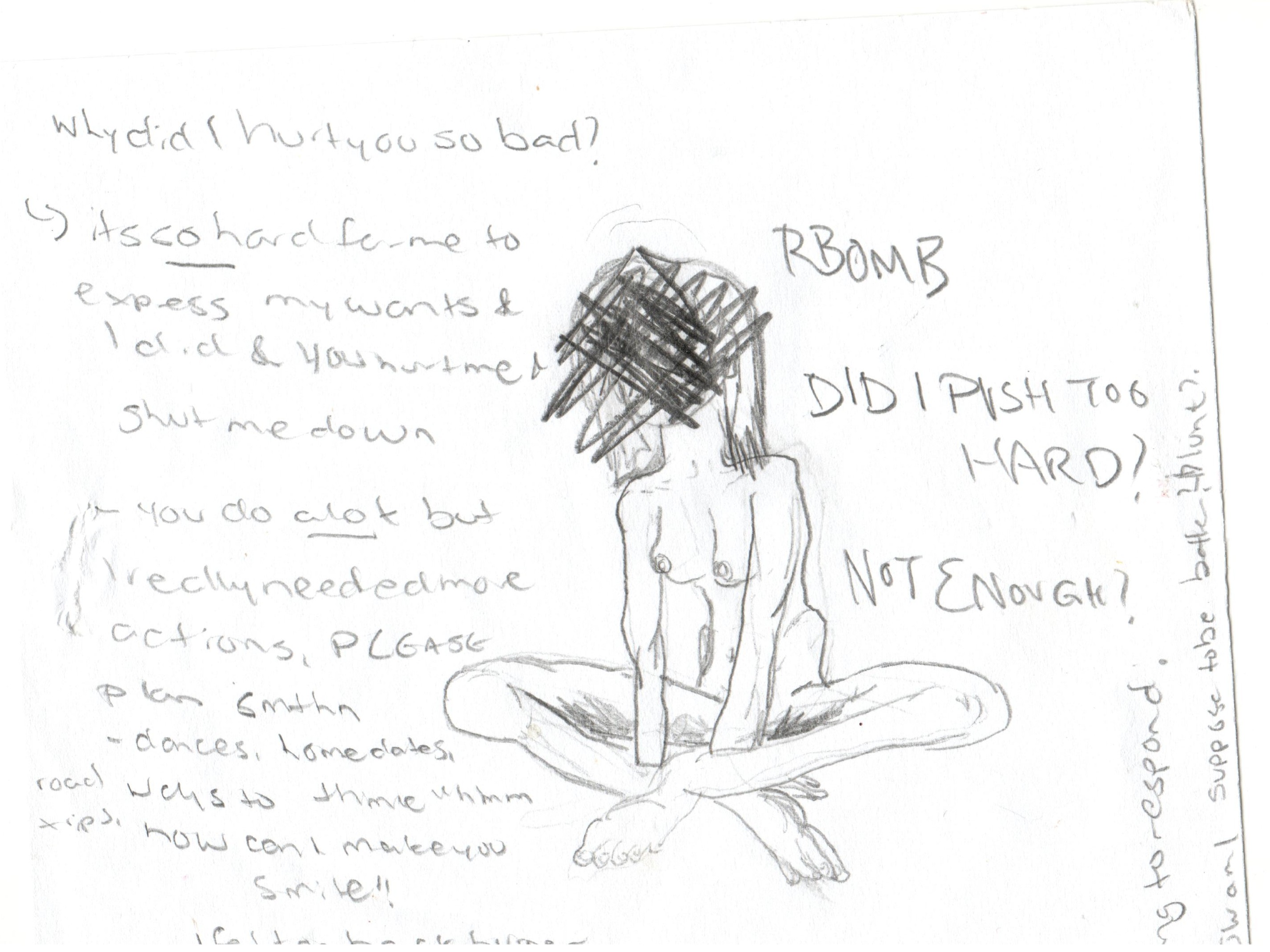

Ally Zlatar, Exerts from Diary, 2021

Artist's Interviews

Interviewing a diversity of artists who explore Eating Disorders in their work and their personal experiences were selected to discuss and encapsulate the varying differences in their Eating Disorder experiences. Purposive sampling aims to provide a heterogeneous outlook on peoples’ experiences and their self-reflections and interpretations and meanings over time, such as existential issues, feelings, and values.

Artwork Creation

When first embarking upon this project, I was purely interested in the capabilities of painting to communicate the depths of the Eating Disorder illness and the potential of autothnographic artworks to represent that experience. Thus, drawing on my own experience through personal stories, texts, and images as autoethnographic research data, I aim to foreground the sensitive nature of the subject matter by providing a personalized visual account of the eating disorder experience(Ellis et al.,2011).

Findings

Lack of Genuine Understanding of Eating Disorders

The predominant perceptions that have saturated public knowledge have always been medical and societal fields regarding the cause, experience, and recovery process of Eating Disorders. I draw from my research, interviews, and art creation that this lack of knowledge regarding Eating Disorders has been detrimental to society as people do not understand the struggle of a person with an Eating Disorder which in turn invalidates individual experience and hinders the approaches to people sharing their stories.

My art responds to my Eating Disorder experience in a variety of ways. I explore the darkest fears and pains that lay within my illness and the unbearable pain that I endured through my work. Other works examined the control over my body, a way to cope with trauma, as well as an avenue to increase safety and acceptance. As we can see, art has a pivotal role in this dialogue. Creative expression is a vital form of research in this discussion. It can communicate and open conversations when we are often too afraid or unable to effectively express how profoundly our feelings and experience can impact us.

Implications of Experience as a Source of Knowledge

As I re-examine the experiences that occurred throughout my Eating Disorder experience and the subsequent self-destructive behaviour, echoing sentiments that they never felt good enough, never felt satisfied, never felt as if they fitted in, and never felt as if they were pretty. I tend to believe my Eating Disorder never leaves a person.

During the process of art creation and developing my personal narrative, I provide my perspective of what the embodied experience means to me. My stories added unique insight into what an eating disorder is, and how it has affected my entire life. I continue to struggle with this illness and am uncertain about my future regarding my Eating Disorder and life in general. My words and artworks development reminded me that my story is not over, and those reflections are no more than a glimpse of my yesterdays. It reaffirms to me that I have learned and grown which is the best one can hope.

Recommendations: Eating Disorder Treatment

The research indicates that there appears to be extraordinarily little effort made by the artistic voice to address eating disorders. It might be beneficial for the institutions to include art literacy curriculums to help provide individuals with the skills necessary to analyze, question, and challenge the information they receive daily from the societal media. In addition, to provide them with the skills needed to avoid stereotyping and role-casting, I would also suggest that the public institutions and media industries provide content that how self-image, identity, gender roles, and racial and ethnic roles are formed.

Fostering voices that do not adhere to the traditional perceptions of the suppressed female body and creating art and educational content to allow others to discover their own unique voice and allow them to use it. Listening to the liberated voices of the few who choose to challenge the perpetuated societal vision of thin, I observed that it is an ongoing battle that needs to be nurtured and cared for constantly. To fully recover the first step is to fight the societal standards and regain individual voices through the recognition and acceptance of self as being imperfect, realising they still have much to offer to the world as flawed but valuable human beings.

I think for myself, and others, recovery treatment was not how I found my voice, it was through my art that I gained strength and we need to foster diverse outlets to recovery to help people to recover by drawing upon their own inner strength and change their perception of themselves. So medical institutions can provide their students with the knowledge and tools necessary to form an individualised voice. The scope of such an analysis could go beyond behaviour practices between staff and patients but could extend to hiring practices of personnel by placing more arts-based staff in the treatment team.

Mary Rouncefield The Dress To Die For, Mixed Media, 120 x 50cm, 2015.

Recommendations: The Art World

What I hope the audience can take away from this research is that Eating Disorders can manifest and exert control in a diverse number of ways, but the essence of suffering is universal. As for the arts community, galleries, museums, and arts programming, these institutions have a responsibility to help portray this illness as authentically as possible. The artistic voice has so much potential to contribute to our understanding of mental health and what I hope is that going forward galleries and museums will not shy away from these difficult subjects.

There is a duty as educators and cultural hubs to handle them with the care and sensitivity they need, especially to the public. Often, we steer clear from these as they may be triggering, but through the work today I hope you see how impactful art can be in this conversation. And lastly, we need the individual voices heard. What makes my research unique was that my positioning was able to examine, create and share the depth of the Eating Disorder experience with the public. However, my voice is not the only one that needs to be heard. Eating disorders are not a quick fix to lose weight but, they are deeply embedded in the individual. As one can see it is detrimental to the livelihood of someone and to treat individuals, we need to treat them and the illness with the utmost severity and respect. Not all experiences are the same. Yet, they all share a common struggle; that they do not choose to suffer, but they do.

Ally Zlatar, The Bones of Paradise, 2022